How Three Shanghai Engineers Created the Next Fashion Nova in the U.S.

From Shanghai to the U.S.: the Rise of LovelyWholesale

Highlights:

LovelyWholesale was established even before SHEIN, and both brands capitalized on the rise of U.S. social media — LovelyWholesale with Facebook, and SHEIN with Pinterest.

Since its 2011 launch, LovelyWholesale's GMV has reached hundreds of millions, backed by 6 million followers globally, including 4 million on Facebook alone.

The brand's focus on Latina and Black women in the U.S. emerged naturally through Facebook ads, driven by customer demand.

SHEIN perfected its supply chain by 2018, while LovelyWholesale only realized its importance that year, leading to a delayed move to Guangzhou.

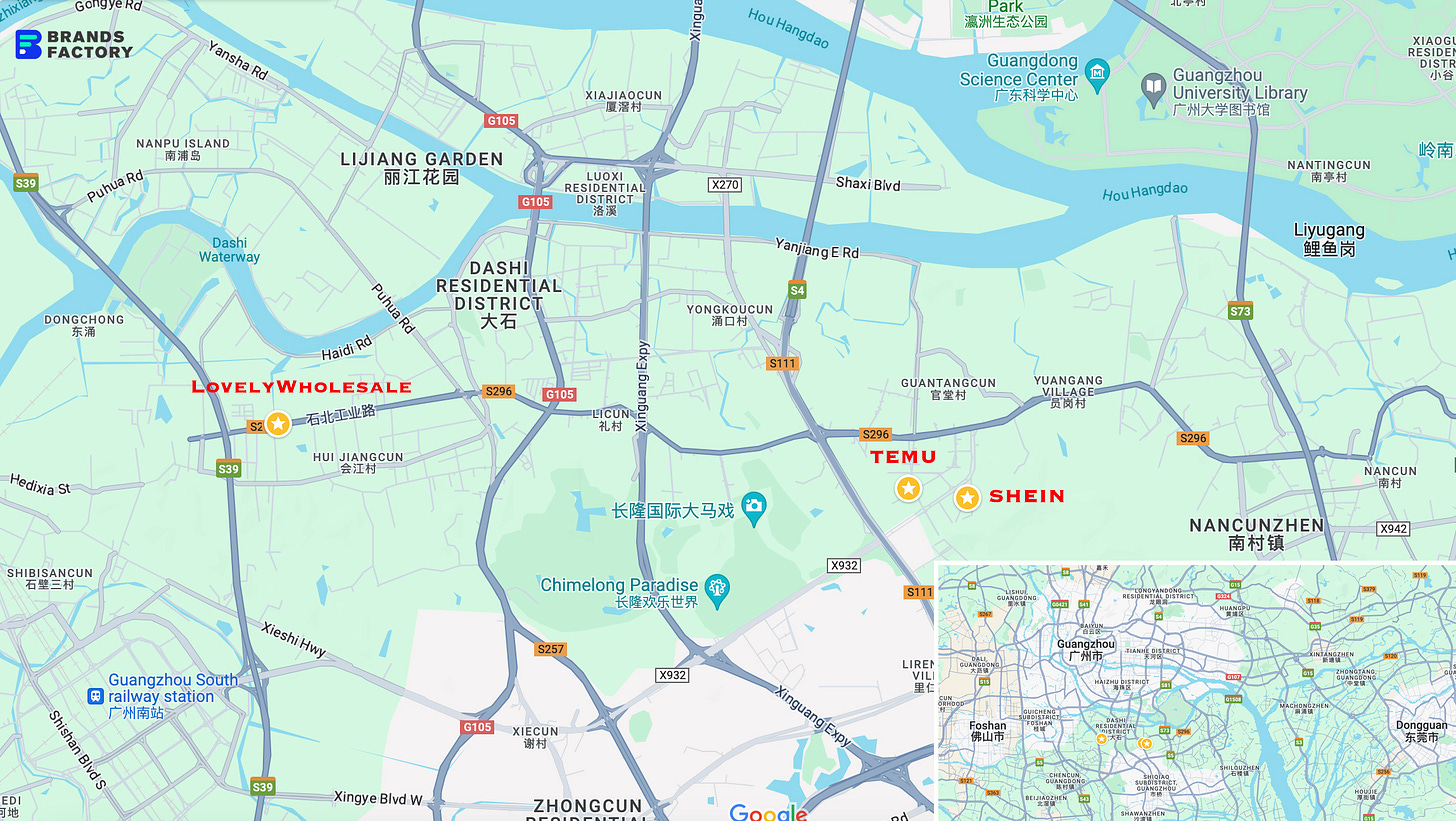

With the rise of Chinese e-commerce, LovelyWholesale has joined SHEIN Marketplace and TEMU to broaden its market.

Who, you might ask, is LovelyWholesale? While not widely recognized, this fashion brand has captured the hearts of Latina and Black women across the United States.

The brand's origin is even more surprising — it was founded by three male engineers in Shanghai. After graduation, their first venture was selling jade on eBay. In 2011, they launched the LovelyWholesale website.

By 2016, LovelyWholesale's gross merchandise volume (GMV) had soared to hundreds of millions of dollars. The brand's influence has also grown, with more than 6 million followers across various global medias, including 4 million on Facebook alone.

LovelyWholesale was founded even before SHEIN. Its co-founder, Guo Le, also knew SHEIN's founder, Sky Xu, in their early years. Both brands made it big by riding the wave of U.S. social media — LovelyWholesale with Facebook and SHEIN with Pinterest.

How did a Chinese startup end up targeting such a niche market of Latina and Black women in the U.S.? How did they amass 4 million followers on Facebook? What's their strategy for marketing overseas? How did they tackle supply chain challenges? And why has SHEIN pulled so far ahead?

Recently, we had an exclusive interview with Guo Le to delve into these questions.

Pioneers in the Game

Brands Factory: Could you walk us through the founding of Pinteng?

Guo Le: My two partners and I were college classmates. After graduation, I went to work at Huawei, while the other two started selling on eBay. I eventually joined them, and we founded Pinteng in Shanghai in 2008. Back then, we sold anything and everything on eBay. One of my partners is from Nanyang, a place known for jade, so we sold some antiques and, in the fall and winter, we sold boots.

Brands Factory: So at first, you didn’t plan to focus on clothing? You just sold whatever was available.

Guo Le: We launched our DTC site in 2009, keeping an eye on what was selling well on eBay. We tried beauty products, boots, and antiques, but antiques had too small an audience, and shoes took up a lot of inventory space and were costly to fulfill. Eventually, we realized that clothing was the best option — it’s small, cheaper to ship.

Brands Factory: You were probably one of the first to set up a DTC site, right? There wasn't even Shopify back then, right?

Guo Le: Yeah, Shopify hasn't appeared yet. While there were few e-commerce platforms in China, we built our own website. We were running DTC sites from 2009 to 2011.

Brands Factory: Was there much infrastructure for cross-border clothing businesses back then?

Guo Le: We didn’t really think about that at the time. There was supply, mostly through 1688. There were early cross-border platforms like DHgate, but they were more like marketplaces. Very few DTC site like us.

Brands Factory: So you didn't really have a concept of branding back then — it was more about just listing clothes online for sale?

Guo Le: Exactly. We simply applied the same approach we used on eBay to our DTC sites. Later, we went through the phase of experimenting with multiple sites. It began in 2017, and by 2018, we saw many companies in Shenzhen booming with this approach.

We were also thinking, "we've done well so far, so could we replicate this success ?" Our target users are pretty small and limited to the U.S., so we knew growth would eventually hit a ceiling. We need to make change.

Brands Factory: So you began focusing on mass listings.

Guo Le: We weren't actually aiming to do mass listings. Instead, we were thinking about creating more brands like LovelyWholesale in the white market or other niche categories.

Ride Social Media Wave in U.S.

Brands Factory: You were one of the first in China to get into the cross-border fashion business, right?

Guo Le: Yes, we started quite early. Around the same time, Romwe, which later became a sub-brand of SHEIN, was also emerging. Romwe was originally run by a company in Nanjing, adopting the multi-site strategy with a bunch of brands. Other early players included LightInTheBox and Globalegrow. We were fortunate to start early and experienced the peak and boom of the industry.

Brands Factory: When did you start to feel like the market was really taking off?

Guo Le: To be honest, we didn't have a strong sense of the industry being in a boom. Everyone knows we target people of color — Latinos and African Americans — but that was more of a coincidence in how our user base developed. We weren't particularly focused on people of color while doing the Google paid ads, and the ROI on Google keywords was pretty high back then.

Brands Factory: How high are we talking?

Guo Le: Generally around 5-6.

Brands Factory: That's impressive.

Guo Le: Indeed. It was around 2012 or 2013, when we noticed that category-specific keywords on Google were yielding good ROI and sales results. Google traffic was primarily about targeting those ready-to-buy customers in the marketing funnel. At that time, we didn't really think about who was buying. It wasn't until 2014, when we began working with Facebook ads, that we saw a significant shift towards people of color in our user base.

Brands Factory: How did that happen? You weren't even designing clothes specifically for these people, so why did they start buying from you?

Guo Le: It all started when we began running ads on Facebook. We noticed two main changes. First, when we were using Google, most sales were made on PCs. But when we moved to Facebook, sales started shifting to mobile devices, showing the rise of mobile internet.

The second change was our user base. Facebook ad's targeting features played a role here — unlike Google, Facebook has more user data as it's social commerce-oriented. As people made purchases, Facebook used that data to target and reach similar and related groups, gradually revealing our core audience.

Brands Factory: Did you ever make a trip to the U.S. to meet your customers and understand what drives them to buy your clothes?

Guo Le: At the time, we didn't really have that idea, but we did take a quick look around. Mostly, we relied on surveys to understand their preferences. Later on, as Facebook and Google introduced more developed tools for analysis, we noticed that our repeat customers were pretty focused. So in a way, it was the customers who chose us.

Brands Factory: How many followers did you have on Facebook then?

Guo Le: Around 4 million.

Brands Factory: A single account with over 4 million followers — that's really something.

Guo Le: It's mostly because we got started early. When we hit 1 million followers, Facebook approached us to create a success story showcase. We noticed then that most of our followers were over 30, with many being Latino and Black. Facebook saw this trend too, recognizing that our audience was pretty focused, so they made us a case study.

Brands Factory: In some ways, your early social media strategy seems similar to what SHEIN did. Did you look into what they were doing back then?

Guo Le: SHEIN's first big wave of traffic came from Pinterest. At that time, Pinterest had a strong affiliate system where you could post there and drive traffic to your site. SHEIN, back then it was still SheInside, cleverly tapped into this and took over 80-90% of that traffic. Afterwards SHEIN moved to Instagram, and as Facebook grew, we all started ads there.

Brands Factory: So in a way, SHEIN grew alongside social media's golden era.

Guo Le: Exactly, before 2020, everyone involved in cross-border e-commerce was riding that boom. We hit a snag when running multiple sites: traffic was cheap and grew fast, but supply couldn't keep up. When you launched a product, it could sell hundreds or even a thousand units the next day, and no supply chain could keep up with such rapid demand.

Brands Factory: What did this lead to in the end?

Guo Le: In the end, it resulted in site closures. Facebook ads would get suspended, and Shopify would shut down sites. We had been with Shopify for over a year, built a team of 30-40 people, and managed up to ten sites at one time. We faced internal conflicts as the operations and sales teams clashed. Sales wanted to capitalize on the traffic, but fulfillment was an issue. Sites kept getting shut down, making it feel like we were always starting over. We had to wait until inventory was in place before continuing with marketing, which was a tough balance to strike.

Brands Factory: In a way, it was also due to the overwhelming flow of traffic.

Guo Le: We had to make sure we could handle all the orders and get all of them shipped out.

Left Behind by SHEIN

Brands Factory: When did you first realize the need to build your own supply chain?

Guo Le: By 2016, the fashion industry already developed a substantial network of supply chains for on-demand manufacturing. It was mostly informal initially, with many small workshops run by couples.

Brands Factory: People say SHEIN was the first to establish a flexible supply chain for clothing. So you were doing the same thing at the same time?

Guo Le: At first, we sourced products from AliExpress and 1688. Our first suppliers were small family-run businesses that took small orders of 30 or 60 items. Many of our suppliers were based in Quanzhou, and the supply chain there grew alongside our business.

In this process, SHEIN nurtured many small suppliers. As it expanded, SHEIN switched to bulk orders because handling scattered orders was tough due to size variations and restocking issues. SHEIN was ahead in realizing how critical the supply chain is. You can't keep the whole business going with small, scattered orders.

Cross-border supply chains aren't something you can just buy with money; it takes time and mutual adaption.

Brands Factory: How did SHEIN's approach differ from yours, since you also realized how important a flexible on-demand supply chain was?

Guo Le: We were just a few years behind. Most companies end up being late. When the traffic surge happened, SHEIN took on the tough and demanding task of managing the supply chain.

Brands Factory: I've also heard that it was quite challenging for SHEIN to negotiate with these clothing factories back then.

Guo Le: Exactly. Our cross-border model works by collecting payment from users upfront and then paying suppliers, who need to make the goods for us. This means suppliers have to invest in the process. Those willing to invest eventually began working with us.

From 2015 to 2018, SHEIN was busy building and perfecting its own supply chain. We only came to understand this fully in 2018 while working with Shopify. It was also during this time that we moved our supply chain operations to Guangzhou to be closer to our suppliers.

Brands Factory: So it's about two or three years later than SHEIN.

Guo Le: Right.

Follow the Routine of Fashion Nova

Brands Factory: What was your annual revenue back then?

Guo Le: It was no more than 1 billion RMB ($140.17 million), with multiple sites included.

Brands Factory: By 2019, it was quite a significant number. When did you decide to build a DTC brand?

Guo Le: Honestly, it was our users who pushed us in that direction. At first, we were just committed to building something long-term and didn't even think of ourselves as a brand. But around 2018 or 2019, as we focused more on LovelyWholesale, we took things a bit further.

We went beyond simple surveys and started inviting customers to join our online meetings, and their passion really got to us. In a way, our two brands were all driven by our consumers. By 2019, customer satisfaction had become a core value of our company.

Brands Factory: How do you define a brand?

Guo Le: To be a brand, first and foremost, you need market share — you must ensure that your products reach your target customers. That’s the most important thing to consider. Secondly, you must differentiate yourself. Brands like Halara and Cupshe have thrived until now because they have specific target audiences and have built up strong barriers around their niches.

Brands Factory: After targeting minority groups, did you make any changes to your supply chain and design?

Guo Le: At first, we didn’t have a clear product strategy. We operated similarly to other cross-border companies — if something sold well, we’d create similar products. It wasn’t until around 2015 or 2016 that we started to better understand our customers and reflect that in our products. In 2018, we got a chance to visit Eifini, a renowned domestic womenswear brand. That was when we started to learn what it really takes to build a fashion brand.

Before that, our approach was pretty broad, but from that point on, we began to focus on what it really means to be a clothing brand, like how to organize product assortments and spread out marketing resources. After 2019, we put more effort into making LovelyWholesale a solid fashion brand.

Brands Factory: You mentioned creating bestsellers before. How do you approach that?

Guo Le: Before 2019, our strategy was more reactive—we would quickly copy anything that was selling well in the market. But there’s another way, which is based on a deep understanding of your users.

We also learned from Halara. Their product line was incredibly focused, with just one main item — the everydaydress yoga pants — and all their influencers were promoting it. We tried in a similar way. Back then, there weren't any basic items on our websites, though for domestic brands, basics can make up 10% of their stock and sometimes up to 50% of their sales.

We also looked at Fashion Nova, a fast fashion e-commerce brand in the U.S. that caters to the Black community with basic items. Most of what SHEIN sells are basics too, like tank tops or camisoles for just a few bucks. We even studied SHEIN's production and found that they don't do anything with more than three processing steps, as it would increase costs and make it harder to maintain quality.

Brands Factory: How did things turn out?

Guo Le: We quickly hit 1,000 sales a day on our independent site. Before that, 100 sales a day was enough for us to call it a hit. After that, our standard for a hit product became 1,000 daily sales. We poured a lot of influencer resources into this, but honestly, it wasn’t that difficult. I think it’s more about having the right understanding.

Brands Factory: Which platform’s influencers are you talking about?

Guo Le: Initially, we mainly focused on YouTube and Instagram. By 2020, we were also on Facebook, and later, when TikTok started taking off, we shifted our focus there.

Working with influencers was effective at first, with a high ROI. But it's a labor-intensive job; one person can only handle few influencers, and by the time we tried to scale up, the results had already dropped off. So, most of the time, influencer marketing doesn't work out for us — you can't really measure how much revenue it brings in.

We started working with influencers around 2015, and for five or six years, there was hardly any return. Before TikTok became commercialized in the U.S., the results from influencers were very limited and could barely cover the costs of two or three staff members.

Brands Factory: Any tips for influencer marketing?

Guo Le: The key is to scale up. Sales isn't the top priority initially; it's more about finding influencers with high engagement. If they interact well with their audience, sales will follow. To see any results, you need to reach those with a certain basis — about 1,000 videos per month for 3-6 months.

Influencer marketing is easier to scale than live streaming. Success in live streaming is tough to duplicate. On TikTok, live streaming might make up 10-20% of the market, but most sales still come from influencers.

DTC sites have a natural edge in influencer marketing; it's much cheaper than traditional ads. With just one day's worth of your ad budget per month, you can reach hundreds of thousands more people. Plus, unlike ads that users often scroll past without stopping, influencer content stays there and is something people actually pay attention to.

Adapt to SHEIN and TEMU

Brands Factory: What made you decide to bring LovelyWholesale to TEMU?

Guo Le: Two things about TEMU really impressed me. First, they have a long-term vision, looking at things over a 3-5 year span, which is different from others I've met who think money alone can fix things fast. My biggest fear was jumping onto a marketplace that talks big, and then I’m stuck with unsold inventory. The second thing is that they've got enough funds to back it up, which put my mind at ease.

Brands Factory: Women's fashion doesn't seem to be TEMU's strong suit right now, does it?

Guo Le: Exactly, their initial success came from African Americans in the U.S., followed by a focus on Amazon-like products and home goods.

Brands Factory: For a while, TEMU was really pushing for clothing sellers, trying to compete with SHEIN.

Guo Le: Yeah, they planned to focus on fashion, hiring three to four hundred people just for that. But once they launched, they quickly saw that home goods took off, outpacing clothing.

Brands Factory: You also joined SHEIN later on. When did they invite you?

Guo Le: They reached out to us when they were rolling out their fully-managed service. We were among the first to get invited, even before TikTok. We started on it around February or March last year.

Brands Factory: How are your sales performing on SHEIN?

Guo Le: SHEIN has a wide product range, but the African-American market is still relatively small there, so our sales are mid-level at best. Most of SHEIN’s focus is on the white demographic. For instance, some sellers we know in Guangzhou sell over 10,000 items a day on SHEIN, primarily to white customers.

Brands Factory: As a DTC brand, how do you feel about selling through other channels?

Guo Le: Before 2020, what we did, what SHEIN did, and what many other cross-border peers did was pretty muck like TEMU. I used to think of us as the TEMU for minority groups, and SHEIN as the TEMU for white people.

Our customers are very price-sensitive, which is why they moved online in the first place. So it makes sense that they would also go to an "online TEMU" for the same reason. Where you sell depends on where your customers are, and if my customers are there, that's where I'll be.

From 2020 to 2021, as traffic on DTC sites started to decline, we began to feel some pressure. That's when I realized that what really matters is getting our labelled products into the hands of our customers.

Brands Factory: 2020 to 2021 seems to have been a tough time for cross-border fashion brands.

Guo Le: During the pandemic in 2020, we experienced a rapid growth thanks to platform subsidies and quickly expanded our team from over 100 to more than 400 people, which led to the only major crisis we've faced in over a decade. At one point, we were even struggling to pay suppliers.

It's easy to think that rapid growth was due to our own skills, but it was actually more about the subsidies. Once those subsidies began to dwindle and the U.S. raised interest rates, our customers, which were already financially fragile, felt the squeeze. Changes in Facebook's algorithm also hit us hard, causing a sharp decline in our sales and making it much harder to attract new customers.

Many brands that experienced a surge during 2020 and 2021 did so mainly because of subsidies, rather than their own branding, team, or marketing efforts.

Brands Factory: You've been in China's cross-border industry for a long time. Over the years, you've probably seen a lot of ups and downs

Guo Le: Indeed. In the beginning, many companies collapsed because they operated in borderline legal areas; some tried to pivot but failed, sticking to gray area. The second wave of firms, like JollyChic, couldn't survive the competition. Those in the third wave mostly couldn't make it through the downturn.

The problem was that they didn't build core competencies like a solid supply chain, so when the market's growth slowed, they couldn't survive.

Overall, the cross-border e-commerce was quite rough before 2020. Everyone was just selling stuff, and it didn't feel like there was much competition. That's why 2020 is often seen as the first year of the era of brand globalization.